Across the misty peaks of the Alps and the deep waters of Scotland’s Loch Ness, two enduring legends have captivated imaginations for centuries: the Tatzelwurm and the Loch Ness Monster. One is a stubby, cat-faced reptile said to slither through mountain caves; the other, a serpentine behemoth rumored to lurk beneath a Highland lake. While separated by geography and form, a provocative new theory suggests these cryptids might share an ancient origin tied to the Roman Empire’s Alpine campaigns—and a misunderstood viper guarding forgotten treasure.

The Tatzelwurm: Alpine Enigma

In the rugged ranges of Austria, Switzerland, and southern Germany, the Tatzelwurm—derived from the German “Tatze” (paw) and “Wurm” (worm)—is a creature of whispered tales. Descriptions vary: a snake-like body, two to four short legs, and a feline head with sharp teeth or a venomous hiss. Folklore from the 18th and 19th centuries paints it as a solitary predator, blamed for lost livestock and eerie encounters. A notable account from 1779 tells of Hans Fuchs, a Swiss farmer who stumbled upon two Tatzelwurms, only to succumb to a fatal heart attack shortly after. A 1934 photograph by Balkin, showing a coiled shape near a log, fueled speculation, though it’s widely dismissed as a hoax.

Naturalists have long sought to explain the Tatzelwurm. Some propose it’s a distorted memory of a large salamander or an adder glimpsed in alpine fog. Others see it as pure myth, a cautionary tale for shepherds. Yet its persistence in oral tradition hints at something more.

The Loch Ness Monster: Scotland’s Aquatic Mystery

Far to the northwest, the Loch Ness Monster—or Nessie—has reigned as a global icon since the 1930s, when a grainy photo of a long-necked shape in Loch Ness sparked a frenzy. Sightings date back further, to the 6th century, when St. Columba reportedly calmed a “water beast” in the River Ness. Modern accounts describe a plesiosaur-like creature, with a serpentine neck and humped back, gliding through the loch’s 755-foot depths. Despite sonar scans and countless expeditions, no conclusive evidence has surfaced—only tantalizing blips and tourist fervor.

Skeptics attribute Nessie to misidentified otters, logs, or waves, while believers cling to the idea of a prehistoric survivor. The loch’s murky, peat-stained waters keep the mystery alive, much like the Tatzelwurm’s shadowy alpine haunts.

A Roman Thread: The Haute Route Hypothesis

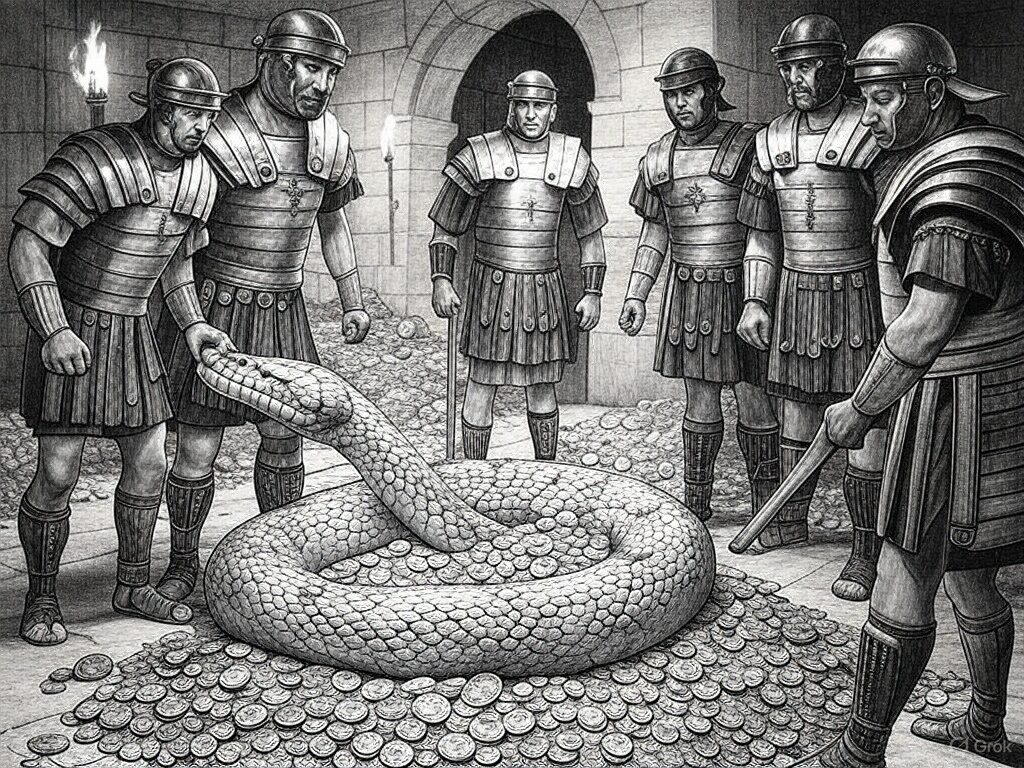

Could these disparate legends share a common root? Dr. Elena Voss, a historian at the University of Bern, offers a bold hypothesis: the Tatzelwurm may have originated as a Roman-era guard animal, specifically a large viper, deployed along the Haute Route—a perilous Alpine pass connecting Italy to Gaul. During the late Republic and early Empire, Roman legions traversed this corridor, transporting gold, silver, and supplies through what’s now Switzerland’s Pennine Alps. Banditry was rife, and Voss suggests the Romans might have enlisted local wildlife as a deterrent.

“Vipers are native to the Alps—fast, venomous, and territorial,” Voss explains. “A particularly large specimen, perhaps exaggerated in size by fearful locals, could have been tamed or tolerated to patrol campsites and caches. The Romans were pragmatic; they used dogs and falcons—why not snakes?” Over time, she posits, these “guard vipers” morphed into the Tatzelwurm of legend, their hissing and striking amplified into tales of a monstrous hybrid.

What of Nessie? Voss speculates that Roman traders or displaced legionnaires, moving north through Britain, might have carried stories—or even a living specimen—of this Alpine guardian. “A gravid viper could have reached Scotland’s waterways,” she says. “Adapted to a new environment, its descendants grew larger, their legend evolving into the aquatic Nessie we know today.” The theory stretches biology—vipers don’t sprout legs or necks—but aligns with how myths migrate and transform.

Science Meets Legend

Zoologists remain skeptical. “The Tatzelwurm’s two legs don’t match any known viper,” notes Dr. Hans Müller of Zurich’s Natural History Museum. “It’s more likely a cultural memory of an adder or slowworm.” Nessie, too, defies easy explanation; no reptile or amphibian fits its profile in Loch Ness’s cold depths. Yet the Roman connection intrigues archaeologists, who point to scattered finds—coins, weapons—along the Haute Route as evidence of its strategic use.

No Roman texts mention snake guards, but the absence isn’t definitive; much of their frontier logistics went unrecorded. If Voss is right, the Tatzelwurm could be a living echo of imperial ingenuity, its Loch Ness cousin a distant ripple of that legacy. For now, both creatures remain elusive, their secrets buried in mountain stone and lake silt—perhaps alongside a lost Roman hoard, still waiting to be found.